Wilson's Phalarope

General Description

Of the three phalaropes in Washington, the Wilson's Phalarope has the longest bill and legs. The female in breeding plumage has a gray back with chestnut and black on the wings. She has a bold, black stripe running from her bill across her eye and down the side of her neck. Her head is gray above the dark stripe and white below. The front of her neck is salmon-colored. Her rump and undersides are solid white. Males vary in brightness, but are gray above and white below, with a white throat and face. The back of the male's neck is brownish, and his face is white, bisected by a dark eye-line. In breeding plumage, adults of both sexes have black legs. During the non-breeding season, both sexes look similar--gray above and white below, with yellow legs. Their faces are white, and their throats are gray. In flight, they are solid white below. Their wings are solid gray, with no white stripe. They have white rumps and light gray tails. Juveniles look similar but are mottled gray-brown above. They keep this plumage for a very short period of time, so juvenile plumage is not often observed in Washington.

Habitat

Wilson's Phalaropes are found mostly on fresh water, but during migration they can also be found in small numbers on salt water. They breed in shallow, prairie wetlands in the northern US and southern Canada. During migration, they inhabit shallow ponds, flooded fields, and sometimes mudflats. Wilson's Phalaropes winter on large, shallow ponds and saline lakes in southern South America.

Behavior

These active birds pick small bits of food from the water's surface. When swimming, they spin in tight circles and create upwellings of food, although Wilson's Phalaropes do this less than the other two phalaropes. In comparison to Red and Red-necked Phalaropes, Wilson's Phalaropes forage more often in shallow water or on shore. They regularly occur with American Avocets and Black-necked Stilts, but they forage in denser habitat and run about more actively than other shoreline-foragers.

Diet

Wilson's Phalaropes eat aquatic insects and small crustaceans. When they are on saline lakes, they eat brine shrimp and brine flies.

Nesting

Females arrive on the breeding grounds before males. When the males arrive, the females compete for mates. Some females attract multiple males, but monogamy is more common. The male builds the nest, which is a scrape lined with grass, concealed in dense, tall grass or sedge near the water. After laying four eggs, the female leaves the male to provide all parental care. He incubates the eggs for around 23 days and tends the brood after they hatch. The young leave the nest within a day of hatching and find their own food.

Migration Status

Female Wilson's Phalaropes leave the breeding grounds after they finish laying eggs. Males follow as soon as the young are independent. They migrate to staging areas on large western lakes (Summer Lake and Malheur Lake in Oregon, and Mono Lake in California) where they molt before their long journey to South America.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population of Wilson's Phalaropes at 1,500,000 birds. They are listed on the Audubon~Washington watch list as a species-at-risk. Much of their prairie breeding habitat has been lost due to the destruction and draining of marshes. Concentrating in a few major staging areas during migration also puts them at risk. They do shift and adapt their breeding range to take advantage of new habitat. While they no longer breed in some areas (Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge in Pierce County is one example), they have expanded into many new areas across the West. This adaptability will help the Wilson's Phalarope fit into the changing landscape. These birds do not seem to be as flexible about staging areas, and the protection of these lakes is important to maintain the species at its current numbers.

When and Where to Find in Washington

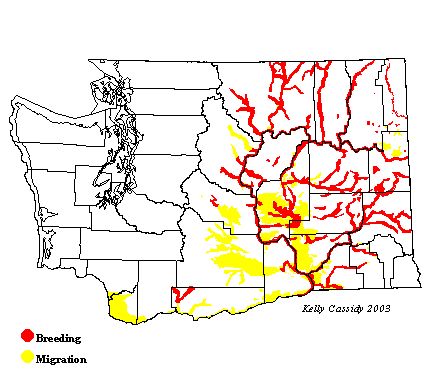

Wilson's Phalaropes are most easily found in eastern Washington, where they are fairly common breeders in appropriate habitat--mostly east of the Columbia and Okanogan Rivers, especially in the Potholes area (Grant County) and the Okanogan Valley (Okanogan County). Breeding Wilson's phalaropes have also been found in some years in the Ridgefield and Nisqually National Wildlife Refuges and in the Everett area.

Wilson's Phalaropes are rare visitors to Washington's coast from late April to early October. These migrants are seen more commonly in western Washington in spring than in fall. In eastern Washington, a few start to arrive in early April, and numbers build throughout the month. By late April, they are common. They stay through July, but numbers drop in August, and they are rare by September when the last migrants leave for the winter.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | U | U | U | U | ||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | |||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | ||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | C | C | C | C | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius